AN ELEPHANTINE RIVER

Posted on

No trip to Mandalay would be complete without a cruise on the Irrawaddy river, or the Ayeyarwady, as it is known as in Burma. The name is a form of Airavata, the sacred storm-cloud elephant, mount of Indra. It is also known as the Road to Mandalay, thanks to Kipling’s poem.

We boarded our battered old boat with some difficulty and a great deal of help. As you can see, there’s no easy way on, and when your boat is the farthest from the shore, you have the added pleasure of having to hop from boat to boat until you get to yours, much as happens to Ashok towards the end of my novel, The Moon’s Complexion – okay, that was Kerala, but the principle’s the same. The incident in the novel was based on my own experience. I thought it was a one-off. Little did I dream of a dejà vu experience in Burma. The Indian boats were sturdier.

Once on board we set out for Mingun some 11km along the river. We had the vast watery vista all around us and life as it is lived on the greatest river in Burma. As with all rivers in this part of the world, the Irrawaddy serves as laundry, washroom, carwash, dishwasher and swimming pool for little monks.

During the dry season the many sandbanks on the river turn into mini-industrial sites. Itinerant families set up camp on them and dig for sand. Boats full of sand ply the water, and the sandbank still look like cliffs. The bulk of the sand appears to end up in Singapore where it is used for land reclamation and building. The effects on the ecosystem and on the villages along the river are now giving rise to concern as the effects are tangible, the diminishing sandbanks affecting fish stocks and the lives of villagers.

The river is navigable along much of its length and is important for transporting commodities such as water melons and bamboo rafts. On the banks shanty towns tumble higgledy-piggledy along the water’s edge.

The half-completed Pahtodawgyi pagoda at Mingun stands near the riverbank like a massive hill of red sand visible from afar. Intended to be the largest pagoda in the world it was never completed, due to an astrological proclamation that king Bodawpaya, who commissioned it in 1790, would die upon its completion. So Burma never secured the record. That honour when to Thailand, with the construction of the Phra Pathom Chedi in the 19th century.

It’s not until you get right up to the Pahtodawgyi that you can see that it really is man-made. But first you have to get off the boat.

No bowing to tourist-comfort here. As in Mandalay, no jetty to step out onto. Just a drop to the muddy shore and a raised bank beyond, that leads up to the village.

But help was at hand. The boatmen have it sussed. A simple plank, and for lily-livered land-lubbers an ingenious banister. What more do you need?

We headed first for a closer look at the Pahtodawgyi. Quite formidable, its dark sides rising over the landscape and dwarfing the sizeable white temple next to it. We could have walked to the top of the Pahtodawgyi, but there was enough to see in the village without forcing my poor old bones (still aching from Heho) to make a strenuous climb in bare feet and midday heat to the top of a half-finished ruin. And yes, it was a ruin – a couple of earthquakes have cracked the sides, so it really does seem to have been a bit of a white elephant in the past, though now it’s a useful ploy to sell to tourists. And historically it is interesting. What would these past monarchs not do to glorify themselves? It’s the same the world over.

The largest pagoda in the world required the largest bell in the world, and sure enough, a bell was cast to fulfil this requirement. Unlike the pagoda, the bell was completed and remains undamaged, another of the ‘sights’ of Mingun. It weighs nearly 200,000 pounds and has a diameter of over 16 feet. Scrambling underneath it is meant to bring you luck. I didn’t try it.

Arguably even more interesting is the 19 th century white Hsinbyume (also known as Myatheindan) Pagoda. The latter is interesting architecturally, representing the seven layers of celestial mountains, leading up to Mount Meru, the home of the gods. It’s also quite a climb to the top, but most of the stairway is covered and the view is impressive. The top terrace is guarded by a series of Nats peeping out of little caves in the balustrade. It was at this temple that the cracks began also to appear in the health of our group, one lady, a doctor herself, managing to get to the top, but promptly collapsing. For a while I wondered how ever we were going to get her down, but eventually she rallied and made it back through the seven celestial mountain ranges to base camp.

But it was the start of a difficult few days for her, and she was the first of several others picked off by the dreaded Burma Belly, or, since they were German, I suppose that should be Myanmar Magen syndrome. Pat and I appeared, amazingly, to be immune. Was it the tough, British constitution? Well, no, in fact reading the instructions that came with our doxycyline antimalarial antibiotics, I discovered that these same drugs are prescribed to ward off travellers’ stomach problems. The German group members had poo-pooed the idea of antimalarials. But now the joke was on them, as they tumbled like skittles with the squits, while we stormed through without a twinge.

The people of Mingun were colourful and fascinating. A woman collecting water sported the traditional haircomb of the area; a nun hurried past - nuns in Burma wear pink robes. And a group of children, including a little monk, were in festive mood.

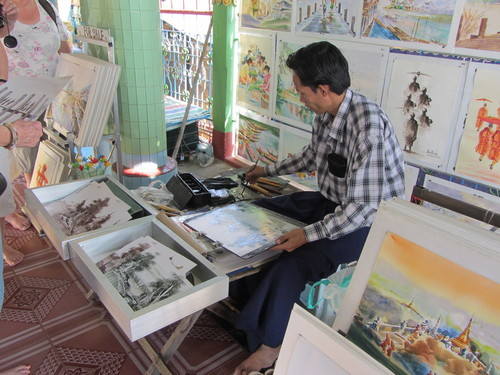

Mingun is a strange little place. The village spreads a couple of kilometres along a dirt road running parallel to the river. Most of it consists of little stores full of touristy things – wooden puppets, stylised paintings of monks, and so on. Less obvious items are also on sale: king coconuts for drinking, interestingly potted plants and there’s even a computer class on offer. Once you have reached the end of it, having climbed to the top of various pagodas in the heat en route, you have to get back to the boat. Bullock carts are on hand. I said I would absolutely and in no way make an idiot of myself. And besides, I felt sorry for the bullocks.

Of course, I ended up having to eat my words. The carts take loads of four, and if I’d carried on protesting my three exhausted buddies would have had to walk back too. It wasn’t exactly a comfortable ride, but okay, I admit it, it was an experience, and it beat walking.

Dambulla. Sri Lanka

Dambulla. Sri Lanka