ONE CLIMB TOO MANY? Sri Lanka Part 10

Posted on

Dambulla is probably not the first place that rolls off most tongues when it comes to naming UNESCO World Heritage sites in Sri Lanka. I guess Sigiriya and Polonnaruwa are at the top of the list – simply because they have been more accessible over the last couple of decades than Anuradhapura, the largest and earliest of the major sites.

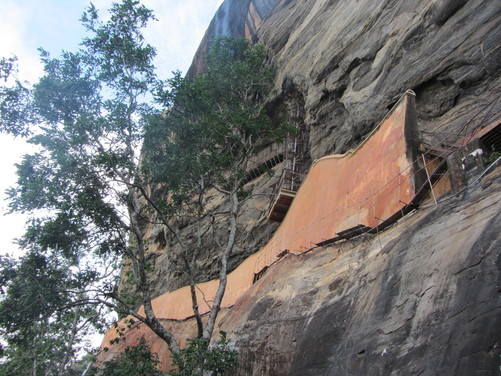

The only reason, as far as I can see, why Dambulla isn’t right up there at the forefront, is because it is a smaller site, with arguably less diversity than the other places. At Dambulla there are no ancient citadels, great dagobas or ruined palaces. There are simply five cave temples cut into a granite escarpment on the side of a mountain.

Simply? Let me rephrase that. There’s nothing simple about Dambulla. I’m biased because I love it, although not all my experiences there have been wonderful.

My first visit was in 1969. It wasn’t a World Heritage site then (it was inscribed in 1991) – not at all set up for tourists. My memories of the cave temples from that time bear no resemblance to those of my subsequent visits. All I remember from 1969 is one dark cave, with Buddha images lurking in the half-light. The whole place infused with an air of mystery. That was, until we tried to leave the cave. Our way was barred by a monk shaped like a sumo wrestler, hand outstretched, demanding exit payment. Enough to turn anyone off religion!

Back to the present. The drive to Dambulla from Sigiriya only took around half an hour – enough time to rest tired limbs that had just climbed the Rock: or putting it another way – enough time for tired limbs to stiffen and seize up!

Since my last visit in 1996, there has been an addition at the foot of the Dambulla site. The Japanese, in their wisdom, have contributed a Golden Buddha, so massive that it can be seen from the steps on Sigiriya. A pleasing addition to the landscape? Not to my eyes. I have to remind myself to try and look through the ‘period eye’ – in other words, to see it through the eyes of a contemporary Sri Lankan Buddhist. It doesn’t help. This product of Far Eastern Mahayana Buddhism is a world removed from the refined art of Sri Lankan Theravada. The nearest I’ve seen to it in Sri Lanka, is the giant Shiva at the Hindu Temple in Trincomalee. But the latter is not out of place amidst its riot of Hindu eccentricity, whereas the Golden Buddha is a total incongruity in its setting at the base of gorgeous Dambulla.

The Golden Buddha is sat atop a new museum of Buddhism (you enter through a monstrous mythological creature’s mouth) , which apparently houses some information, copied paintings and Buddhist images. Any time spent there would have taken time from the caves, so I decided to give the museum a miss and began my ascent up the steps to which Upali directed us after we’d purchased our tickets.

Something was different, unfamiliar but it wasn’t until we reached the temple complex, , 350 feet up the 600 foot rocky outcrop, that I realised what had happened since my 1996 visit, and why Upali had made such a fuss about the difficulty of the climb. Try as I might, I couldn’t actually remember having climbed many stairs on my previous two visits. Was my memory really that bad? Now I made my way slowly up the 800 or so stone steps . Hard work, yes, though once again the plateaux between flights gave respite. The flights were much wider than the narrow stairways of Sigiriya, so you were less in danger of clashing with other visitors!

The views were stunning – this time the reverse of the morning’s panoramas from Sigiriya. Now we looked over the jungle to the rock.

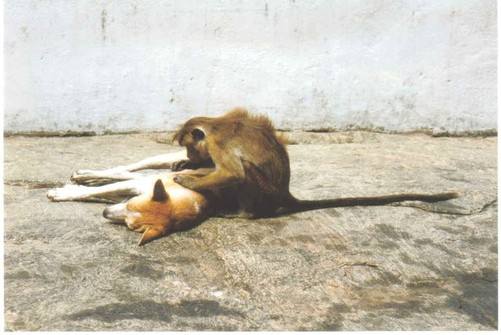

The difficulty of the climb was further alleviated by groups of macaque monkeys engaged on their daily chores. Mothers were particularly meticulous, grooming their babes on the steps, ignoring hordes of passing pilgrims and tourists. It all made the ascent less arduous and very charming.

Though I was disappointed when I reached the caves, to find no evidence of the dog-grooming activities I’d witnessed in 1996. In fact, no evidence of the beautiful pariah dogs that had found refuge there. Perhaps they’d all gone off for lunch. Or perhaps officialdom had seen fit to remove them. That would be a pity.

At the top we left our sandals before we passed through an entrance building into the paved courtyard in front of the caves.

Now the penny dropped. As I looked out from there I saw a wide, paved slope running up the side of the mountain parallel to the steps. Of course. This was why I didn’t remember the steps. We’d come up the slope on previous visits.

Groups of laughing barefoot schoolgirls in white ambled up the sloping track. In Sri Lanka the girls, not the boys, wear ties as part of their uniform. There’s so much white in Sri Lanka – school uniforms, temple visits – and yet it’s always crisp and clean. How do they do it, especially in the hot, damp climate?

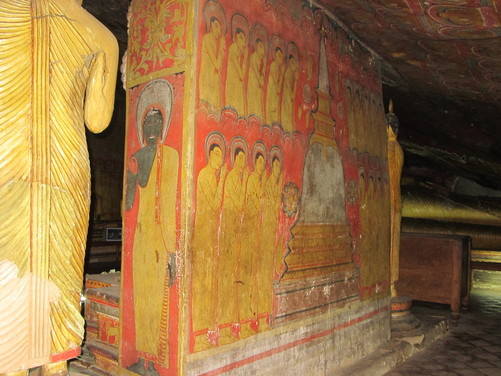

I’m not going to go into huge detail on the caves – for that watch this space, for the eBook expanded version of this blog. If ‘cave temples’ bring to mind Ajanta or any one of the many other overwhelming sites in India, you will have to switch to another mode when you go to Dambulla. The Indian cave temples are true ‘rock cut’ temples, hewn out of solid rock, so massive that their construction is beyond comprehension. Dambulla is not like that – in fact there is much debate about how much is natural cave and how much is man-made. The truth is that no-one really knows, but it’s thought that original natural caves may have been extended. Unlike the Indian ones they do not imitate architecture. In a sense that makes them equally enigmatic. There are five shrines in all, created and expanded over 2000 years. In the beginning they were probably sanctuaries for wandering monks. Over the millennia they were carved out and filled with painted stone and wooden carvings of Buddha images, stupas and kings. The walls and ceilings are also covered with paintings, ranging from simple repetitive flowers and patterns to the Jataka stories and representations of the Buddhist pantheon. These paintings cannot be compared in their delicacy and skill with the priceless Gupta paintings at Ajanta, or the Sigiriya frescoes. They are, on the whole later restorations, many stemming from the eighteenth century. The whole effect though, is delightful, particularly on the sloping, natural-looking ceilings of the shrines. The predominant colours throughout the temples are yellow, ochre, red and gold. Of course they are now restored, which is why they look so fresh and bright, unlike those of my fractured memories from 1969.

Some of the Buddha images are standing, some seated, and among the most impressive are those lying in Parinirvana. The images are all brightly painted, but somehow not garish. There’s a pleasing harmony to them. Because they were carved and assembled over the centuries, some of them are clearly associated with rulers such as Vattagamini Abhaya (1st century) and Nissankamalla (12th century), as verified by accompanying inscriptions and sculpture portraits of the ruler.

It’s a mesmerising place and it was hard to tear myself away and head back down the steps to the waiting van.

Little did we know it when we left Dambulla, but we had one more climb in store before dinner. When we arrived back in Sigiriya the van turned off the main road and bumped down the little one-lane street to our hotel, passing the Sigiriya rest house and continuing passed a reed-and-lotus-covered lake in which the rock is famously reflected. Memories started to stir once more. It dawned for the first time that we had walked along this road – then an unmade track – in 1996, when my niece and I had expressed a desire to swim. The only hotel sporting a swimming pool in 1996 was the Sigiriya Hotel, some half a mile along the track, and beyond where our Sigiriya Village Hotel now stood. On the way we had passed a young elephant with his mahout. We stopped to pat the elephant, who caressed us gently with his trunk. Yes, that's me in white on the true left, and another of our party (not my niece) on the right.

Later, when we returned to the rest house darkness had fallen, and we had forgotten to bring a torch. The moon was new, and shed no light. We couldn’t see anything. The situation was frightening. We had no idea if there were wild elephants around, and we were even uncertain about Tamil Tiger insurgents, since nowhere in Sri Lanka was really safe, and we weren’t that far from the conflict proper. As we stumbled forward, a light appeared. The young elephant’s mahout had come to our rescue with his torch and led us back to the rest house.

So this was in the back of my mind, when returning from Dambulla, we noticed an elephant tummy-deep in the lake, bearing a couple of tourists. It looked such fun – for the elephant as well as the tourists, that temptation (and madness) reared its ugly head. Margot, Pam and I all decided that we couldn’t miss out on this experience. In addition I couldn’t help wondering if this was my elephant from seventeen years ago. He was five years old then, so he’d be in his prime now. It made sense.

Upali established that a ride would last forty minutes, including the bath in the lake and would cost a small fortune. Heinz, being sensible, said that wild horses wouldn’t drag him onto the elephant, but if we insisted on such lunacy he’d wait for us and take photos.

I have issues with the domestication of elephants, which often involves cruel treatment and dreadful conditions. However, this one had the luxury of spending most of its day in the place elephants love best – the water. So I’m afraid I let my principles slip for the first, but not the last, time on the tour.

We were formally introduced to the elephant, whose name was Saman (after a Sri Lankan deity). He looked well-cared for and healthy, and the chains were not hobbling his feet together, as is so often the case. Pam, Margot and I climbed the mounting ladder and settled ourselves on the howdah – if that’s what it could be called. Basically it was a flimsy wooden platform with a rickety bar to hold onto. If Saman decided to lean too far to one side we’d be hard-pushed not to slide straight out and onto the ground – or into the water, especially as we were placed with two of us on one side and one on the other. Hardly makes for an equal load. At this stage we started to worry. This was not going to be a very safe excursion. We headed off up the road, gritting our teeth and hanging on for dear life. Pam and I suddenly had the distinct feeling that the howdah was slipping downwards. We gripped harder and I drew one foot up onto the howdah to give me some grip. Eventually we turned round and the elephant waded into the lake. This was meant to be fun? Pam and I were convinced that the howdah was slipping further – or possibly Saman was trying to roll? It was surely a matter of minutes before we would land in the lake with a large elephant rolling on top of us…

Suddenly the elephant’s owner called from the lake-edge. An exchange of shouts and much to our relief, we headed back to home base, where we rapidly, and angrily, disembarked. We had had twenty minutes of the forty minute trip. Why were we sent back? Not because the owner feared for our lives, but because some more tourists had turned up and the scoundrel thought he’d fit in one more ride before darkness fell.

They demanded a tip on top of the disgraceful price we’d had to pay up front, and were very sullen when we refused to give them one, since we’d only had half the promised time. We kept quiet about the fact that we were actually very relieved to get off. We left with bad feelings so I never did find out if Saman was ‘my’ elephant. But looking at the photographs that were taken of our ride, I can see quite clearly that the howdah was indeed slipping. (that's me at the back with my leg drawn up - trying to stop myself from sliding and trying to look nonchalant!)

This was our last night at the Sigiriya Village Hotel. A meal out, an early night, a feeling of satisfaction that we’d proved that we could indeed tackle Sigiriya and Dambulla in one day. Suddenly the Elephant Incident didn’t seem to matter so much. It would be something to talk about when we got home.

Tomorrow we would be moving on to Kandy.