SIMON SAYS...

Posted on

SIMON SAYS…

A one-man performance by Simon Callow is guaranteed to be a show-stopper, no matter what the subject. I remember being mesmerised by his monologue on ‘Shakespeare and Love’ many years ago at the Oxford Literary festival.

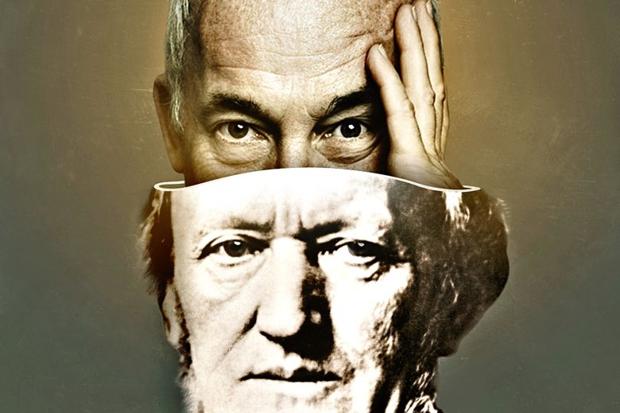

Being a professed admirer of Wagner’s music (though not of the man) I was not about to miss the opportunity to get ‘Inside Wagner’s Head’ through the medium of Simon Callow.

The event is being staged through September at the Linbury Theatre in the Royal Opera House as part of the bicentenary celebrations of Wagner’s birth.

Callow did not disappoint. Aided by an eclectic assortment of scattered props, ranging from a caged parrot to a coffin, he enthralled the audience for one and a half hours, taking us through the life of the most controversial , and arguably the most brilliant composer that has ever lived. Whiffs of music – Wagner, Weber and Beethoven tantalised the senses, never quite resolving before it faded.

The trouble with Wagner is that much about him is so familiar that it’s hard to find something new to say. But Callow presented familiar facts so freshly that they surprised anew. And he did indeed manage to supply some information that I, at least, had not heard before. For instance I did not know that Wagner ‘never tried to lose his Saxon accent’, which Callow conveyed by a subtle hint of Cockney, whenever he quoted Wagner directly. Of course Wagner’s womanising is universally known, but it’s such an entertaining aspect of the man’s character that it bears repetition. There is no better indicator of Wagner’s charismatic power over men as well as women than the fact that he seduced the wives of highly respected and talented men like Wesendonck and Von Bülow right under their husbands’ noses, living in their houses, being supported by them financially, even going so far as to produce two children with Cosima while she was still married to Von Bülow.

Ever the subject of debate and much soul-searching for people like me, is Wagner’s well-documented and rampant anti-Semitism. Callow didn’t dodge this, suggesting, among other things that it may have had something to do with his jealousy of the success of Jewish composers such as Meyerbeer and Mendelssohn in comparison with his own struggles and his frequently impecunious state, largely of his own making. Interesting theory. Wagner, Callow informed us, became swept up in the Germanisation of the German lands, hence his obsession with Teutonic myths and legends. In combatting his own failings and justifying his own passions, Wagner had a whole ethnic group on which to vent his frustration. He regarded the Jews as foreigners, thus not capable of creating ‘German’ art forms. Sounds familiar.

What Simon Callow omitted to say was that anti-Semitism was rife in Europe in the 19th century and Wagner’s views have to be considered in the context of his time. Not that it excuses him. In this respect he was a despicable little man – oh, yes, I hadn’t realised that he was small in stature either.

Callow talked about Wagner’s regard for the philosophy of Schopenhauer, who saw the world as a place of endless pain only to be mitigated by a renunciation of desire.

Ironic, that. If there is one thing Wagner didn’t ever appear to do, it was to renounce desire. However, his last opera, Parsifal, reflects Buddhist, rather than Christian ideas: Parsifal kills the swan and is lectured by Gurnemanz on the sanctity of all life; the attempts by Klingsor’s flower maidens to seduce Parsifal in Act 2 are clearly based on the demon Mara’s tempting of the Buddha; Kundry’s continual rebirth. Other Buddhist references flow forth throughout the opera. It’s Buddhism dressed in a superficial Christian robe.

Callow reminded us that Parsifal was greatly influenced by Schopenhauer ‘s theories. He did not mention that Schopenhauer embraced Buddhist and Hindu thought in his philosophies. It’s a pity Schopenhauer was also anti-Semitic , especially as this vile concept has no place in Indian thinking.

Callow reminded us of a final irony. Although Wagner had initially objected , the first performance of Parsifal was conducted by Herman Levi – a good longtime friend of Wagner’s … and a Jew.

I’ll leave Simon Callow now – go and see the production if you can. It’s fascinating. Tonight I’m off to listen to another Simon - Simon Schama, talking at the Yvonne Arnaud Theatre. I’ll let you know what that Simon says.