Morocco Tour: Points of View

Posted on

Morocco is, of course, more than gold, and all that glisters can also be fool’s gold. It depends on your starting point, and the direction in which you are travelling.

At the moment I am devouring books that our guide, recommended: all fascinating and all contradictory. Nobel prize-winner Elias Canetti’s ‘Voices of Marrakesh’ paints a snapshot picture of the city in the early 20th century – I love it when someone says so much in so few words, the sign of a good writer. Canetti paints his own interpretation onto what he sees. So his descriptions are coloured by thought-provoking flights of fancy. Edith Wharton, on the other hand ('In Morocco') is taking an early 20th century tour of the whole country. I’m not sure I like her. The French can do no wrong, it seems, and that includes her friend the first French resident-general, Hubert Lyautey, who was responsible for changing the six-pointed star on Morocco’s flag to a five-pointed one, and later cosied-up to Mussolini. Enough said.

The third book is a 1980s novel, 'The Sand Child' by Moroccan author Tahar Ben Jelloum. Infused with magic realism this is an addictive read, highlighting the plight of women in an unashamedly patriarchal society, where women count for little and are kept behind closed doors or hidden under tent-like layers of cloth. It speaks for the women of Morocco as 'A Thousand Splendid Suns' speaks for the women of Afghanistan. It is telling that both books were written by men.

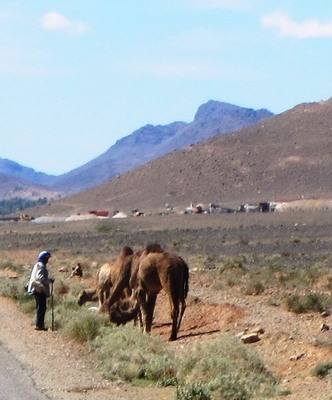

I came to Morocco not knowing what to expect. I felt it would be outside my comfort zone, which lies in a circle encompassing much of the Indian Subcontinent and South East Asia, and was looking forward to the challenge.

The size of the cities surprised me. I suppose I expected Casablanca to be big and brash like all ports, and this is the largest in North Africa, and Morocco’s commercial and industrial heart, but Fes, Rabat, Marrakesh? Somehow, I had a vague idea of donkey-width alleyways hidden behind high walls, veiled women slipping wraith-like in and out of doorways; I did not picture wide boulevards lined with palms, coffee bars and fast food outlets, shopping malls and new hotels like airport terminals. Neither did I imagine the obscenely huge mosque in Casablanca, funded, according to one guide, by the ‘offerings’ of all the citizens, including the poor, in other words, extracted from them as a kind of tax. It could be called stunning, but is, in reality, a grotesque statement of power. Even the immense and beautiful hammam, under the mosque, is, according to our guide, 'just for show and will probably never be used'.

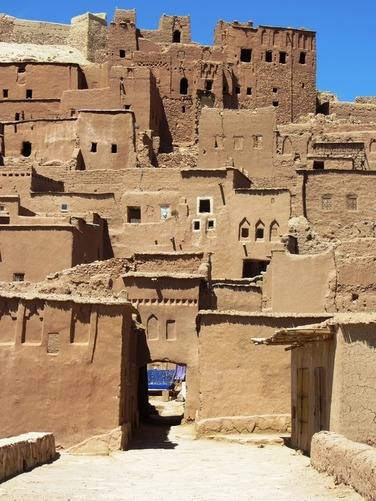

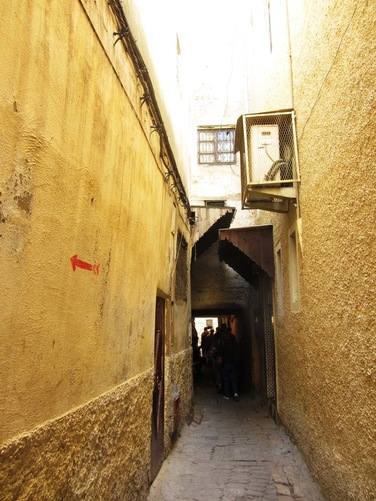

Of course the medinas of my dreams do exist, nestling alongside the new towns. Once I dip inside them they are very much as my imagination foresaw them. The high walls hide secrets. Scarcely a window opens onto the little thorough-ways, for Moroccan Muslim homes face inwards onto their own inner courtyard, families living private hidden lives, their women shielded from prying eyes. Only wooden doorways pierce the blankness of their fortress-like walls, often a large door with a smaller opening set within it, one for family, the other for guests. A carved hand, sometimes attached to the door is a talisman, echoed in ceramic form in every souvenir shop. Echoed also in Jewish tradition, Judeo-Islamic customs are often difficult to disentangle here. Indeed, perhaps the biggest surprise for me was the visible extent of Morocco’s Jewish past: every town has its mellah, where the Jews lived, mostly now sadly depleted of original residents, who left in the mid-twentieth century to pursue a different dream. The houses in the mellah have balconies: opening a vista onto the wider world, unlike that of their introspective Islamic neighbours.

Casablanca: General Lyautey

![]()

The Medina, Fez

The Mellah, Marrakesh

Casablanca: King Mohammed V1 anfd the flag of Morocco

Casablanca: Hassan II Mosque